Treating Knee Cartilage Injuries

Cartilage repair is at the forefront of orthopaedic surgery with new techniques being developed and their outcomes undergoing ongoing assessment.

When orthopaedic surgeons talk about cartilage, we are talking about two different anatomical structures.

Articular Cartilage

Articular Cartilage

Joints are coated with highly specialised “articular” cartilage. This is a lubricated, low friction surface that allows joint movement. This can unfortunately become damaged with injury or as a result of arthritis. If the damaged area is of limited size, it is possible to treat it with a number of developing and established techniques

- The simplest method is “edge stabilisation abrasion or radiofrequency chondroplasty” – a method of arthroscopically (keyhole) treating the damaged unstable tissue to reduce pain and facilitate the limited ability of articular cartilage to undergo intrinsic repair.

- Microfracture or arthroscopic drilling – a method of stimulating the bone marrow to release cells that can “sit” in the cartilage defect and differentiate into cells that produce predominantly “scar” cartilage. This technique is generally reserved for smaller (less than 2cm squared) defects. It is a one stage procedure.

- Combination arthroscopic drilling/microfracture and biomaterial “scaffold” – using a bioengineered substance in combination with the above mentioned technique to produce a more stable healing construct. This substance is generally either a “patch” or gel of collagen/protein. Some work is being done with carbon pads for larger lesions that looks promising.

- Cell-ingrowth scaffolds – new products are being developed that act as scaffolding material for the surrounding healthy cartilage to grow into

- Osteochondral autografts – cartilage and bone can be moved from one area of the joint to another. Auotgraft means that it is the patient’s own tissue that is used. The main problem here is that almost all parts of a joint carry out a role in healthy joint movement. This procedure “sacrifices” the cartilage and bone from one “less essential” area and moves it (normally as a tube of cartilage and bone) to the damaged “more important” area. This is normally an area where more of the body weight is borne.

- Osteochondral allografts – cartilage and bone can be moved (transplanted) from a different person’s (or animal’s) joint to the damaged area of the patient’s joint. Graft survival rates are moderate with this technique

- Autologous chondrocyte implantation – this is a 2 stage procedure where a small amount of cartilage is taken from the patient’s joint at a first operation, and sent for processing in a lab. The cartilage cells (chondrocytes) are encouraged to multiply and specialise (or differentiate) to become good quality cartilage-generating cells in the lab environment. At a second procedure, the cells can then be put back into the damaged area of the joint, normally fixed onto a collagen membrane to facilitate the procedure.

- Replacement of the damaged area with a micro, partial or total replacement.

Meniscal Cartilage (“sportsman’s cartilage”; “the shock absorbers”)

Meniscal Cartilage

There are 2 “menisci” that sit on the inner and outer sides of the knee. Either meniscus is made of resilient fibrous cartilage and has more or less the shape of a “C”. The 2 menisci carry out a very important role of:

a) shock absorption – acting as a cushion, defending the knee from articular cartilage injury

b) load transmission – distributing load to the knee to minimise “peak loading pressures”

c) joint lubrication and nourishment

As a vital part of the joint, the function of the meniscus is to prevent the deterioration and degeneration of articular cartilage, and the onset and development of osteoarthritis. If damaged or torn, it should often be treated. The medial (or inner) meniscus is closely positioned to the medial collateral ligament, which makes it less mobile and it is more prone to injuries.

Research into meniscus repair is of particular interest to Rik and Jamie. “Repair” attempts to stabilise the damaged cartilage to improve the chance that it will heal and continue protecting the knee and its articular cartilage. If a damaged meniscal cartilage cannot be treated, the relative risk of arthritis is significantly increased. This is particularly true for lateral (or outer) meniscal cartilage tears.

Tears are more likely to heal in

- younger patients

- with smaller tears

- treated promptly after injury

On the other side, larger tears in older patients and where treatment is delayed, are less likely to heal.

James is currently auditing the outcomes of the last 100 meniscal repairs he has carried out.

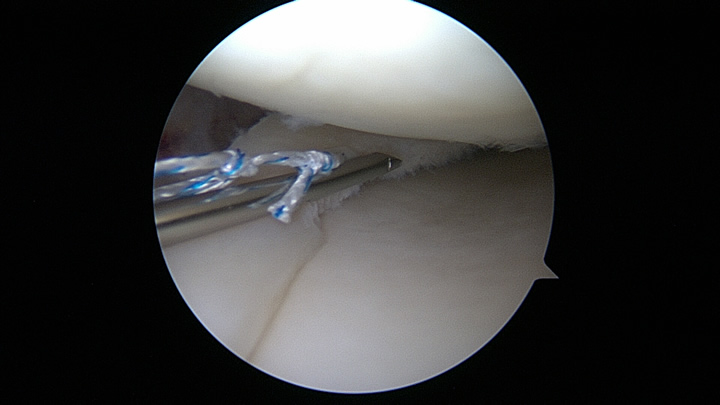

The device for fixing the torn meniscus is an “all inside” meniscal suture (or stitch).

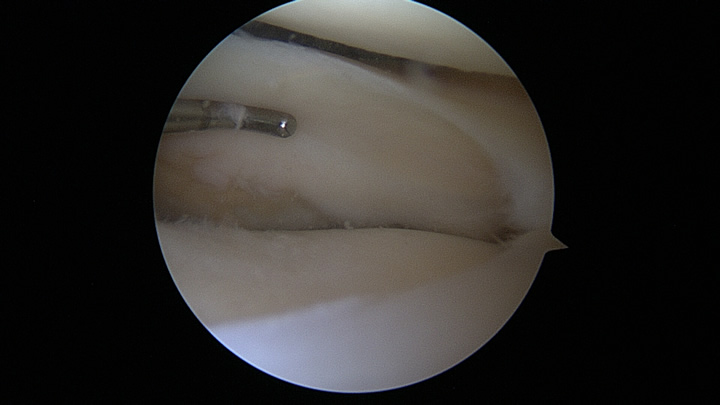

This is the lateral or outer meniscus. It is being probed and inspected for signs of damage. This one is healthy and free of pathology.

Cartifill® for Cartilage Defects

Chondrotissue®

Please click on the links below to view or download the documents:

The cartilage implant for biological cartilage repair

View Doctors Brochure

Patients Flyer

View Patients Flyer